REVIEWS OF OUR FAVORITE WOLF BOOKS

Reviews by Norm Bishop, who served on the Yellowstone Center for Resources team that restored wolves to Yellowstone National Park in 1995.

-

Gordon Haber and Marybeth Hollerman. University of Alaska Press, 2013.

Author Dr. Gordon Haber studied Alaskan wolves in Denali National Park and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve from 1966 until his untimely death in a plane crash in 2009. Marybeth Holleman assembled his writings in Among Wolves.

In his first chapter, Haber observes: “Wolves are fascinating as individuals, but what I find unique is the beautiful, interesting, and advanced structure of an intact family group. Fragmentation of a wolf group through hunting and trapping disrupts this animal’s most prominent characteristic.” And, “(L)earning and tradition are of special importance in wolf society. Consider the length of time young wolves remain dependent on older family members - 25 percent of normal life expectancy…longer than that in most human societies.”

On P. 219, he writes, “Many complex controls operate between predators and prey when they are left to themselves. The result is an animal community characterized by a high degree of vigor, genetic diversity, great variety, and the ability to withstand major natural disturbances such as severe winters. Claims that wolves destroy the very food source upon which they depend are absurd. Nothing of the sort has ever been witnessed in any study of a natural animal community where wolves are the major predators. In short, there is no reason for us to think we must control a natural wolf population. The optimum size is reached by leaving the control solely to the wolves, as research in many areas of North America has demonstrated.”

Under “Ethical Costs, Ecological Values,” Haber writes: “Wolves feature two unusual evolutionary strategies - cooperative breeding and cooperative hunting - that operate primarily through sophisticated interactions and interdependencies within family groups. These close, complex, cooperative relationships cannot be expected to withstand heavy predation, natural or otherwise. Human killing at a rate of 15 percent or higher appears to produce lingering biological impacts even when numbers recover to prior levels - impacts to social structure, hunting, distribution, genetics, and annual mortality rates. Sometimes mortality rates increase sharply after the killing has ended.”

He ends, “In a world of limited resources but increasing human numbers and demands, non-consumptive uses such as watching and photographing may, in fact, have the greatest validity. Viewed in this perspective, we can at the very least insist that the days of aerial gunning, snaring, denning, poisoning, and other types of wolf slaughter - whether called predator control or not - and the resulting degradation of wilderness must remain in our past.”

Norman A. Bishop was on the Yellowstone Center for Resources team that restored wolves to the park.

-

John A. Vucetich Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021.

In his foreword of this book, David W. MacDonald of Oxford University observes that “(T)his is a scholarly book by a clinically intellectual author, steering clear of anthropocentrism and misanthropy….This book is about understanding what counts as a good relationship with nature…” And, “Ultimately, this is neither textbook nor wolf book: it is a paean to nature.”

Dr. Vucetich current leader of Ecological Studies of Wolves on Isle Royale, at 64 years the longest continuous study of wolves the world, has written an analysis in great depth about wolves, moose, and the island wilderness in which they live. He denies that it is (simply) a wolf book. He is right.

This is a book about the history of thought about our relationship with our natural world; about concepts like the balance of nature as seen by ancient Greeks and Romans, through centuries of theoretical and theological interpretations, to the present; and wilderness, as perceived by Abraham, by the Puritans, by conservationists like Olaus Murie, and by current environmental organizations.

In lively stories, Vucetich chronicles the findings of the Isle Royale wolf studies back to the beginnings, citing the first researchers - Durward Allen, L. David Mech, Rolf O. Peterson; then his own work of 25 years.

Along the way, he acquaints us with the biography of Isle Royale; its geological origin, its vegetation, and its inhabitants, from microbes to moose, algae to Abies balsamea (balsam fir), and the food chains that connect them. He does not omit the profound effect that a changing climate has on the lives of Isle Royale animals.

Who but an imaginative and perceptive observer of animal behavior would recognize that wolves dream. Vucetich observes, too, that: “A wolf is a living creature, with a perspective, memories of yesterday, an interest in how tomorrow turns out, joys and fears of its own, and a story to be told. Those realities create obligations for us to be concerned for their lives.”

Vucetich introduces us to the Ojibwe view of wolves: “(T)he Ojibwe, Native Americans whose homeland includes Isle Royale…believe the wolf is their brother - not metaphorically but literally.” (They) “…profess the wolf as a principal source of knowledge.”

No, this is not a textbook. But in it, you will discover that wolves can tell us much about our relationship with nature.

Norman A. Bishop was on the Yellowstone Center for Resources team that restored wolves to the park.

-

Greystone Books, 2019

With his groundbreaking life story of Wolf 8, Rick McIntyre demonstrates his stiletto-sharp insight into wolf behavior and ecology that captures not only the biology, but the social role and personality of an individual wolf that Rick followed for most of its life.

Wolf 8’s life is a saga of triumph and tragedy, tribal warfare, love and loss, sagacity and survival, evoking Shakespearian and Biblical story themes as well as revealing new insights into the complexity of lupine existence.

This book offers the reader an opportunity to substitute fears and crass assumptions with facts and charming stories about wolves.

You will be richly rewarded by reading each detail in The Rise of Wolf 8 patiently, because they all lead to a chaotic conclusion in Chapter 27, The Battle of Specimen Ridge, in which Wolf 8 and his son, Wolf 21, meet in a gripping climax to an altogether stunning story.

This is not Rick’s first wolf book; his earlier books, A Society of wolves: National Parks and the Battle Over the Wolf (Voyageur Press, 1993), and War Against the Wolf: America’s Campaign to Exterminate the Wolf (Voyageur Press, 1995), earned him a solid place among writers on wolves. In the first of these, Rick documented Denali’s National Park’s East Fork pack, descendants of wolves studied by Adolph Murie from 1939 to 1941, which Rick observed during his 16 summers at Denali.

Murie’s study of the relationship of wolves and Dall sheep took him 1,700 miles on foot in 1939. Over the course of his study, mostly of the East Fork Pack, he gathered skulls of 829 sheep, and analyzed the contents of 1,174 wolf scats, classifying 1,350 food items, mostly caribou and Dall sheep. He documented it all in his 1944 classic, The Wolves of Mount McKinley.

In Yellowstone, Rick watched and recorded the behavior of wolves seasonally from 1995 to 1998, and year round from April 1999 to 2019. He spent 7,895 days afield, equivalent to 21.6 years; at one stretch, going out every day for over 15 years. That’s 89.6% of the days the wolves have been in the park since their release from the pens in March of 1995. He tallied 100,000 wolf sightings during that time; some days watching from pre-dawn to last light.

In the summers of 1994-1997 as a season naturalist he gave talks on wolves, and from 1998 through 2008 during his earlier days with the Yellowstone Wolf Project, he gave at least 1,300 talks. From 2008 to 2/18/18 he gave 1,789 talks. That would total talks he gave from 1995 to 2018 to over 3,000. Over 28,000 people attended those talks. He recently estimated that he helped over 100,000 people see wolves. It is astonishing to realize that he always took time to help visitors share the experience of observing wolves, in spite of his intense concentration on the wolves themselves.

Norman A. Bishop is a retired Resources Interpreter and member of the Yellowstone Center for Resources team from 1985 to 1997 that restored wolves to Yellowstone National Park. Norm led Yellowstone Association Institute wolf courses from 1999 to 2005, and found Rick infallibly kind and helpful to his classes.

-

Greystone Books, 2020

Wolves emerged in North America 800,000 years ago, but it wasn’t until quite recently that the life story of a gray wolf was told. Wolves lived in harmony with aboriginal Americans for millennia, then were annihilated everywhere EuroAmericans went. A sea change in public attitudes toward wolves led to their restoration to Yellowstone National Park in 1995. As soon as wolves were on the ground in Yellowstone, park biologists began an intensive research program that has yielded hundreds of scientific journal articles and several books. In parallel with those studies, one focused individual, naturalist Rick McIntyre, dove headlong into observing them at every opportunity. Rick had already written a book on Denali’s wolves, A Society of Wolves, and a chronicle of “America’s Campaign to Exterminate the Wolf” in his War Against the Wolf.

Rick’s quarter century of observations yielded a charming and revealing book in 2019, The Rise of Wolf 8, about the ascent to leadership by an unlikely pup, one of the first born in the Yellowstone area. His second book on Yellowstone wolves, The Reign of Wolf 21: The Saga of the Legendary Druid Pack (2020), is available from greystonebooks.com. or your local bookstore. In 2021, his latest book, The Redemption of Wolf 302, was published.

Why would you want to read it? The saga of Wolf 21’s pack’s struggle for existence, killing animals six to twelve times their size to feed their pups, while defending their turf from other wolves, protecting their pups from coyotes, mountain lions, and black and grizzly bears, is riveting. The Reign of Wolf 21, as revealed by consummate story teller Rick McIntyre, gives readers insights unavailable anywhere else. To accumulate the story, Rick was out in Lamar Valley watching the life of Wolf 21 and that of 21’s parents, progeny, and competitors for nearly every day of the wolf’s entire life. From June 2000 to August 2015, he was out for 5,547 days in a row. Rick’s ability to tell a story is legendary, weaving multiple elements into a single narrative. Short of watching the wolves yourself in the field, you will find Rick McIntyre’s account of the life of a wolf pack riveting. It is both a nature documentary and a docudrama.

Little wonder that Native Americans revered and emulated wolves. The events Rick records so faithfully are similar to what Aboriginal Americans saw as admirable and worthy of imitating: caring for the young at all costs; fighting for the territory needed to sustain the tribe; skill and perseverance in hunting; ignoring pain to keep the family fed.

Scientist Rene Dubos began his 1968 Pulitzer Prize-winning book, So Human an Animal, with: “Each human being is unique, unprecedented, and unrepeatable.” Wolf author Rick McIntyre illustrates, in example after example, that the same is true of wolves.

In The Reign of Wolf 21, we are introduced to the many ways wolves affect other species, from elk to aspens and willows to beavers, ravens and grizzly bears; even songbirds and beetles. Meriwether Lewis recognized wolves as “shepherds of the buffaloes.” Current scientists offer a plethora of ways wolves promote the health of wild ecosystems. Rick McIntyre has expanded our understanding of the wolf’s keystone role in making Yellowstone’s ecosystem complete. It reads like a novel, but is based entirely on astute personal observation. You’ve got to read it to believe it.

Norman A. Bishop was on the Yellowstone Center for Resources team that restored wolves to the park.

-

Greystone Books, 2021

Rick McIntyre’s Third Yellowstone Wolf Story Continues a Peerless Series

When a hockey player scores three goals in a single game, the player may win a hat—or a cascade of hats. In my view, Rick McIntyre has scored a hat trick with his three books on Yellowstone wolves: The Rise of Wolf 8, The Reign of Wolf 21, and now The Redemption of Wolf 302. Each wolf’s story, the first from 1995 and the last from 2009, adds breadth and depth to our understanding of wolves—a species that can well afford more human appreciation of its kind. And happily, there are more books to come.

The hero of The Redemption of Wolf 302 demonstrates one of the most predictable traits of wolves: unpredictability. He first comes to our attention as a rake and a renegade, flitting from pack to pack, breeding with multiple willing females and then retreating to his home pack. Later, he joins packs—always as a subordinate, but managing frequently to break the “rule” that the dominant pair are the only wolves in a pack that breed. Finally, having survived to an age well beyond that of the average wolf, he shows the world that he is a responsible, caring, self-sacrificing adult. In so doing, he fulfills his legacy in the manner and spirit of his predecessors, Wolf 8, Wolf 21 and others.

Do you think that, among wolves, you will find relentless killers? Or that wolves can be caring, selfless parents? Right both times. In The Redemption of Wolf 302, we witness an invading pack besieging the dens of a resident pack, keeping the new mothers from reaching food or water until all their pups die. The invaders follow up by killing the resident pack’s adult males.

In a nearby valley, we track the lives of warrior wolves that pin their enemies and then let them live. Those same warriors allow their pups to defeat them in wrestling matches and exhaust themselves carrying meat to pups from carcasses that may be ten miles from the pups’ den.

If you think a wolf blunders around, blindly guided by instinct, think again. In The Redemption of Wolf 302, it becomes obvious that a wolf learns from birth to death. She relies on experience to avoid a second kick by a vigorous bison that flipped her fifteen feet through the air, turning her 360 degrees before she landed. Wolf 480 uses an ancient Chinese battle tactic to win over an opposing group that outnumbers his: Charge as though you are the stronger unit, and win by spreading fear among your adversaries.

If you believe that elk are easy for wolves to kill, read McIntyre’s account in The Redemption of Wolf 302 of the Slough dominant pair both getting stomped, the male twice, by an elk cow they’d chased into a creek. After one wolf was able to grab a hind leg, other wolves rushed in as the elk got into water so deep they had to swim. Finally, the dominant female swam up and got a good bite on the elk’s throat. As six wolves surrounded her, the elk died and drifted to a sandbar, where 20 wolves fed on her. Rick observes that about 1% to 5% of hunts are successful.

In The Redemption of Wolf 302, we learn about the hazards wolves face as they hunt to feed their families. McIntyre needs 7 1/2 pages to describe the “occupational injuries” 302 and others have. Eight Druid pack wolves tried to kill a bull elk that took a stand in the river and shook them off. The wolves gave up and paddled to shore. It is dangerous for 100-pound wolves to take on prey up to ten times their weight. Wolves get gored by antlers or horns. They get kicked in the head and lose teeth. Or, like Wolf 302, get kicked so hard they spin through the air before crashing to the ground. One wolf got butted over a cliff and died. Others were stomped or knocked down; one was kicked down a riverbank and took six hours to recover. Former Yellowstone Wolf Project leader Mike Phillips examined 225 wolf skulls in Alaska; 25 percent had suffered blunt-force trauma. A paleopathologist who examined Wolf 8’s skeleton said, “I do not understand how an animal could live through this.”

In his 1978 classic, Of Wolves and Men, Barry Lopez observes that we all make our own wolves, mostly by our imaginations. We recall the story of the five blind men and the elephant. To one, bumping into the beast’s side, it resembles a wall. To another, touching the tusk, it is like a spear. A third, feeling the tail, says it’s like a rope. The fourth feels the leg and thinks it’s like a tree. To the fifth, feeling the ear, the elephant is like a fan. Fortunately for the readers of The Redemption of Wolf 302, author Rick McIntyre is in command of all his senses, aided by hundreds of other observers, equipped with a 60-power field scope, and has recorded every detail of what he has seen wolves do for more than 20 years; in one period, Rick observed wolves every day for 892 days. Now, we have a complete picture of the wolf.

Two decades in Yellowstone, observing and recording wolf behavior daily—and great skill in telling their story—have enabled Rick McIntyre to reveal to armchair wolf fans the Three R’s of wolves: The Rise of Wolf 8, The Reign of Wolf 21, and now The Redemption of Wolf 302. In this third saga, Rick rewards readers with the heartwarming, heartbreaking transition of Wolf 302 from a rambling rake to a responsible adult to a rear guard ready to die to save his pups.

Wolf stories don’t get better than this.

-

Greystone Books, 2022

Undaunted Courage, or perhaps Against All Odds could have been the title of the first chapter of The Alpha Female Wolf: The Fierce Legacy of Yellowstone’s 06, “Acting Like an Alpha.” In it, 06’s relative, 571, counterattacks alone against overwhelming odds to protect her pack’s pups, attacking three big male invaders from a nearby pack. Author Rick McIntyre keeps us on pins and needles as the three-against-one fight progresses, with a surprise ending. After that, could the stories become more riveting? You will want to read on.

Wolf 06 was unique, unprecedented, and unrepeatable. In Yellowstone, every wolf pack and its members are identified by one or two radio-collared members, and by the individual size, color, markings, and behavior of others. Naturalist-author Rick McIntyre has studied them almost daily for two decades (seven wolf generations). DNA informs biologists of the identity and genetic kinship of most park wolves. All those relationships come to life in The Alpha Female Wolf The fierce Legacy of Yellowstone’s 06. But that’s not the half of it. Tumult, tragedies, triumphs, leadership and love, losses and legacies; all these come to light in this book. Rick saw it all first hand, and conveys it in spell-binding stories that will keep you reading on.

Yellowstone, the world’s first national park, has become the site of an unparalleled experiment in restoration of wolves; extirpated by the 19930s, and studied intensively since their restoration in 1995-1996. For decades, naturalist-author Rick McIntyre has devoted every day to observing, recording, and writing about the lives of seven generations of wolves - unquestionably devoting more time than anyone else in the world to the cause of understanding the lives of wolves. The results: four books, and counting. In 2019, The Rise of Wolf 8. In 2020, The Reign of Wolf 21. In 2021, The Redemption of Wolf 302. Now, The Alpha Female Wolf: The Fierce Legacy of Yellowstone’s 06. It is bound to become a classic.

Small wonder that author-naturalist Rick McIntyre finds the mothering skills of female wolves extraordinary; so did Native Americans, who credited wolves with demonstrating admirable parenting, and emulated them. From the first female to form a pack in Yellowstone after reintroduction, wolf 7, to wolf 06, six generations later, they showed Rick why we now consider the females the leaders of their packs - the alpha wolves. In his 23 years afield, Rick comes to realize that, unlike earlier impressions of leadership within wolf packs, it is not the males, but the females, that make the key decisions about where to den, and when to hunt. He shares his documentation of those facts in story after story in The Alpha Female Wolf: The Alpha Female Wolf: The Fierce Legacy of Yellowstone’s 06.

Rick McIntyre’s The Alpha Female Wolf: The Fierce Legacy of Yellowstone’s 06 tracks the life of a wolf who demonstrates that wolves, like aboriginal humans who emulated them for millennia, live in families for whom they willingly sacrifice their lives, and whose care is central to their pups’ well-being. As aboriginals did, wolves defend their hunting grounds with their lives, and go to great lengths to avoid interbreeding. That means males and females alike must venture forth in search of an unrelated mate, at great personal peril. In the face of continual threats of starvation, attacks by neighboring wolves, and brutal weather, play is one of their major activities. One wolf biologist characterized them as “happy oafs.” Yet, they learn and apply lessons that help them survive many threats to their well-being. Wolf 06’s life adventure is worth analyzing, as author McIntyre did, to better understand this amazing creature with whom we share the earth.

When will we ever learn…the true nature of wolves? Ojibwe of the Great Lakes saw them as brothers. To European settlers, they were agents of the devil. In 1928, Henry Beston wrote, “We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals… In a world older and more complete than ours, they move finished and complete, gifted with the extension of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings: they are other nations.” Adolph Murie had studied the wolves of Mount McKinley from 1939 to 1941. He wrote, “The strongest impression remaining with me after watching the wolves on numerous occasions was their friendliness.” Now, with ongoing studies at Isle Royale from 1958, and intensive studies of wolves since 1995 in Yellowstone, we are finally getting a more complete view of how wolves affect the ecosystems of which they are essential members. John A. Vucetich’s 2021 Restoring the Balance and Douglas W. Smith, Daniel R. Stahler, and Daniel R. MacNulty (eds) 2019 Yellowstone Wolves reveal the scientific picture. Rick McIntyre, in his fourth book on the alpha wolves of Yellowstone, digs deeply into the social lives of the wolves, illuminating our view of their true nature. The Alpha Female Wolf: The Fierce Legacy of Yellowstone’s 06 (Greystone Books. 2022) tells us that 06 and her family are both fearsome and frolicsome, surviving internecine strife and territorial wars. Like their ancestors, they also endure injuries from their prey: deer, elk, bison and moose can all kill wolves.

The backstory to Rick McIntyre’s fourth Yellowstone alpha wolf book, The Alpha Female Wolf: The Fierce Legacy of Yellowstone’s 06, is simply staggering. This world champion wolf observer has spent 23 years studying Yellowstone’s wolves in the field - for 8,947 days through the end of March 2022 - seeing wolf on 93.35% of those days. No other observer has recorded the lives of seven generations of wolves as intimately and continuously as Rick has, in chronicling the lives of alpha wolves, climaxed by alpha female 06.

Want the facts about wolves, and how they live? Scientists tell us that one datum point or observation requires replication to verify them as facts. Wolf author Rick McIntyre has written more than 10,000 pages of notes, based on his observations over most of 23 years, and has shared them with us in a series of four books: In 2019, The Rise of Wolf 8. In 2020, The Reign of Wolf 21. In 2021, The Redemption of Wolf 302. And now, The Alpha Female Wolf: The Fierce Legacy of Yellowstone’s 06. It is said that we learn, not from facts, but from stories. Rick knows that, and shares many gripping and poignant stories about wolves that illustrate their lives in intimate detail. In the 06 book, we learn that female alpha wolves are caring, courageous, self-sacrificing, highly discriminative in choosing mates, meticulous in selecting a den site, capable of killing elk six times their size, have the strength, stamina, tenacity, and determination enough to travel 36 miles in a day to carry food to her pups, and yet playful and frolicsome in the shadow of numerous threats to her well-being. There has never been an adventure story starring wolves comparable to this one.

-

Douglas W. Smith, Daniel R. Stahler, and Daniel R. MacNulty, eds. 339 pages, U. of Chicago Press, 2020

In 2020, it has been twenty-five years since one of the greatest wildlife conservation and restoration achievements of the twentieth century took place: the reintroduction of wolves to the world’s first national park, Yellowstone. Eradicated after the park was established, then absent for seventy years, these iconic carnivores returned to Yellowstone in 1995 when the US government reversed its century-old policy of extermination and—despite some political and cultural opposition—began the reintroduction of forty-one wild wolves from Canada and northwest Montana. In the intervening decades, scientists have studied their myriad behaviors, from predation to mating to wolf-pup play, building a one-of-a-kind field study that has both allowed us to witness how the arrival of top predators can change an entire ecosystem and provided a critical window into impacts on prey, pack composition, and much else.

Here, for the first time in a single book, is the incredible story of the wolves’ return to Yellowstone National Park as told by the very people responsible for their reintroduction, study, and management. Anchored in what we have learned from Yellowstone, highlighting the unique blend of research techniques that have given us this knowledge, and addressing the major issues that wolves still face today, this book is as wide-ranging and awe-inspiring as the Yellowstone restoration effort itself. We learn about individual wolves, population dynamics, wolf-prey relationships, genetics, disease, management and policy, newly studied behaviors and interactions with other species, and the rippling ecosystem effects wolves have had on Yellowstone’s wild and rare landscape. Perhaps most importantly of all, the book also offers solutions to ongoing controversies and debates, including contributions from 54 authors.

Featuring a foreword by Jane Goodall, beautiful images, a companion online documentary by celebrated filmmaker Bob Landis, and contributions from more than seventy wolf and wildlife conservation luminaries from Yellowstone and around the world, Yellowstone Wolves is a gripping, accessible celebration of the extraordinary Yellowstone Wolf Project—and of the park through which these majestic and important creatures once again roam.

-

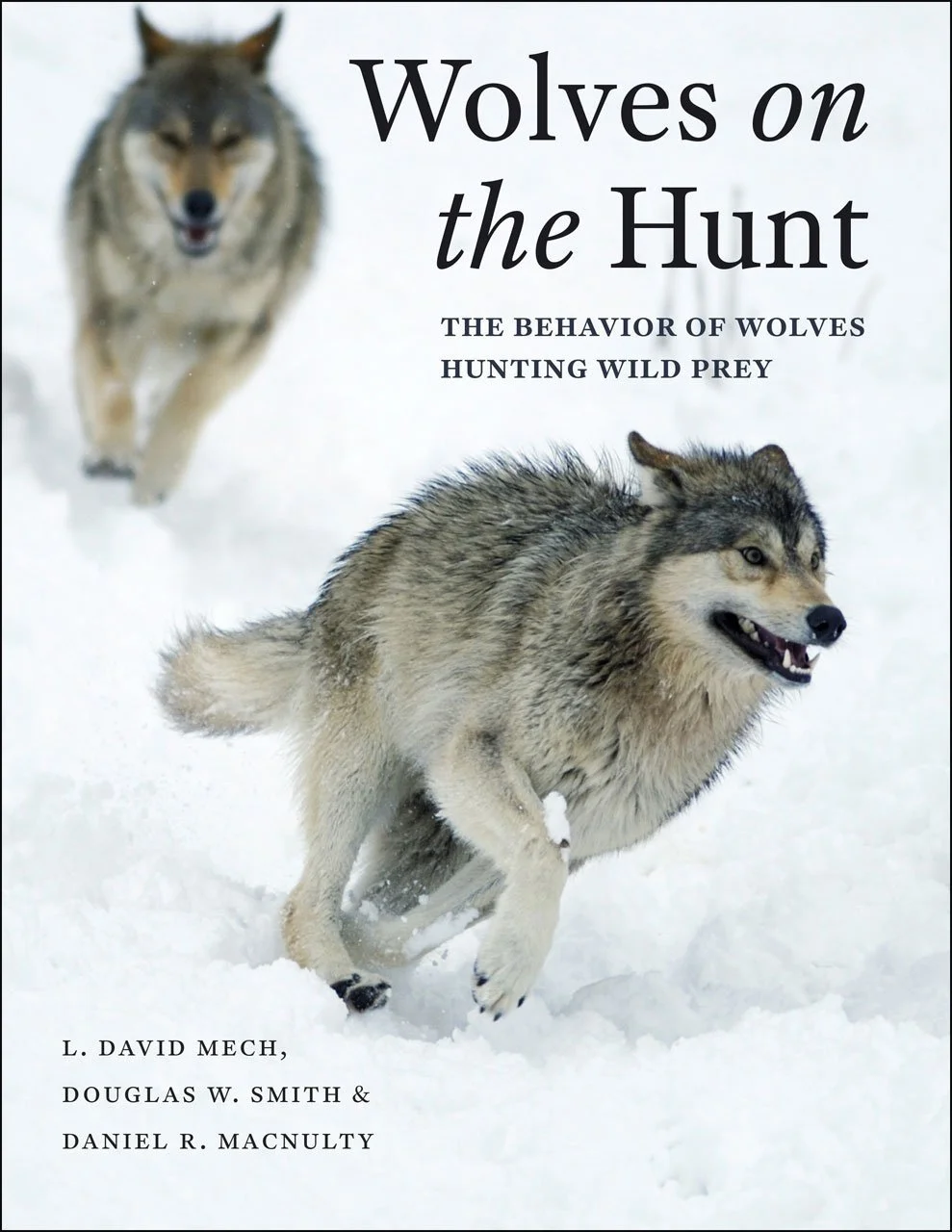

L. David Mech, Douglas W. Smith, and Daniel R. MacNulty, University of Chicago Press, 2015

The authors have condensed 100 man-years of personal observations, plus those of others, into a remarkably comprehensive set of descriptions and analyses of how wolves make a living, and how their prey stay alive in the presence of wolves. The authors reveal, one species at a time, how wolves engage their prey in the game of life and death, in terse descriptions that may cover a couple of minutes, or a couple of days. They also remind us that white-tailed deer, moose, musk-oxen, elk, and bison can each kill wolves in self-defense. They tell us one of their smallest prey, arctic hares, can simply outrun them up steep hills, or out-zig-zag them. The authors provide us with answers to knotty questions like, “Are wolves killing machines?” “Do they kill more than they need?” “Can they kill anything they want anytime they choose?” “Can they live on mice?”

I tallied the number of accounts of wolves hunting different prey the authors selected to share with us: 63 hunts of white-tailed deer; 78 of moose; 56 of caribou; 26 of elk; 49 of mountain sheep; 7 of mountain goats; 7 of bison; 29 of musk oxen; 3 of pronghorn; 1 of a wild horse; 53 of arctic hares; 3 of snowshoe hares; 4 of waterfowl; 4 of mice. That’s 383 accounts of wolves hunting numerous species of prey. If you wonder why there are so few accounts of wolves hunting bison, maybe it’s because it took ten pages to describe those seven hunts, one of which lasted parts of two days.

In reading Wolves on the Hunt, we make a quantum leap forward in our knowledge of wolf hunting behavior. But, as Rolf Peterson observes in his stellar foreword, “There is much that biologists don’t know about wolves, and maybe our ignorance even exceeds our knowledge (how would we know?).